Abused, neglected, abandoned — did Roald Dahl hate children as much as the witches did?

Described as “the world’s greatest storyteller”, Roald Dahl is frequently ranked as the best children’s author of all time by teachers, authors and librarians.

However, the new film adaptation of Dahl’s controversial book, The Witches, warrants a fresh look at a recurrent contrast in Dahl’s work: child protection and care on one hand and a preoccupation with child-hatred, including child neglect and abuse, abandonment, and torture on the other.

Dahl himself once admitted he simultaneously admired and envied children. While his stories spotlight children’s vulnerability to trauma, his child protagonists show how childhood can be an isolating but ultimately triumphant experience.

Anti-child or child-centred?

While Dahl’s fans champion his “child-centredness” — arguing that anarchy and vulgarity are central to childhood — Dahl’s critics have ventured to suggest his work contains anti-child messages.

In Dahl’s fiction, children are often described unfavourably: they are “stinkers”, “disgusting little blisters”, “vipers”, “imps”, “spoiled brats”, “greedy little thieves”, “greedy brutes”, “robber-bandits”, “ignorant little twits”, “nauseating little warts”, “witless weeds”, and “moth-eaten maggots”.

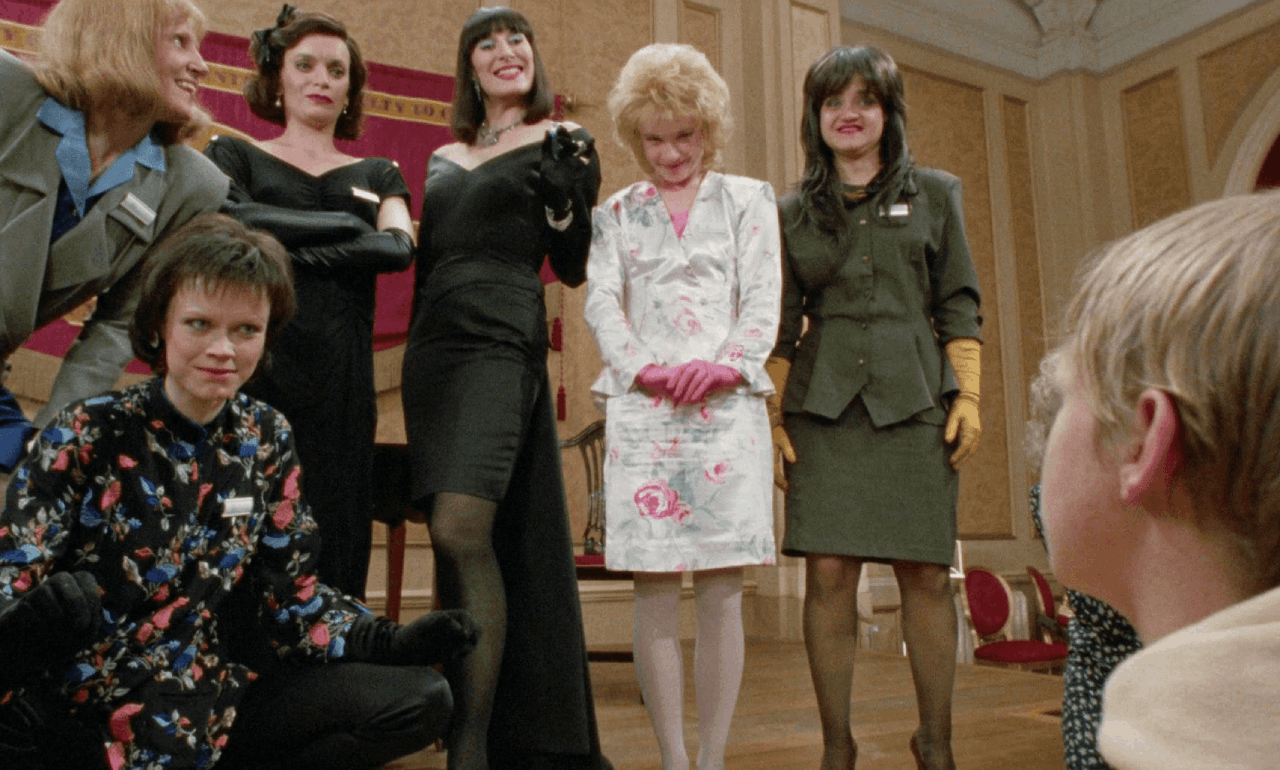

Frightening female character on stage. Children behind.

The cruel and imposing figure of Miss Trunchbull in the stage musical Matilda. MANUEL HARLAN/Royal Shakespeare Company/AAP

With the exception of Bruce Bogtrotter, “bad” children are usually unpleasant gluttons who are punished for being spoiled or overweight. Augustus Gloop is ostracised because of his size. After he tumbles into Willy Wonka’s chocolate river and is sucked up the glass pipe, he’s physically transformed. “He used to be fat,” Grandpa Joe marvels. “Now he’s as thin as straw!”

From Miss Trunchbull to the Twits, Aunts Spiker and Sponge, and even Willy Wonka, many of Dahl’s adult characters are merciless figures who enjoy inflicting physical and emotional pain on children.

In Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, Wonka not only orchestrates the various “accidents” that occur at the factory, but he stands by indifferently as each child suffers.

In Wonka’s determination to make the “rotten ones” pay for their moral failings, he not only humiliates the children (and their parents), but permanently marks the “bad” children through physical disfigurement. When gum-chewing champion Violet Beauregarde turns purple, Wonka is indifferent. “Ah well,” he says. “There’s nothing we can do about that”.

Red-hot sizzling hatred

The Witches is centred around the theme of child-hatred.

“Real witches,” we are told, “hate children with a red-hot sizzing hatred that is more sizzling and red-hot than any hatred you could possibly imagine”. At their hands (or claws), young children are not only mutilated but exterminated.

Indeed, the ultimate goal of The Grand High Witch is filicide: she plans to rid the world of children — “disgusting little carbuncles” — by tricking them into eating chocolate laced with her malevolent Formula 86: Delayed Action Mouse-Maker.

In The Witches, as in many of Dahl’s fictions for children (he also wrote adult erotica), authoritarian figures are revealed as bigoted and hypocritical, or violent and sadistic. Primary caregivers are neglectful or absent.

So the real threats to the child protagonists of The Witches, Matilda and James and The Giant Peach are not monsters under the bed, but adults whose hatred of children is disguised behind a mask of benevolence.

In The Witches, the young narrator initially finds comfort in the fact he has encountered such “splendid ladies” and “wonderfully kind people”, but soon the facade crumbles.

“Down with children!” he overhears the witches chant. “Do them in! Boil their bones and fry their skin! Bish them, sqvish them, bash them, mash them!”

Necessary evil

Although the violence present in Dahl’s work can be easily perceived as morbid, antagonism towards children is a necessary part of Dahl’s project.

The initial disempowerment of the child lays the groundwork for the “underdog” narrative. It allows downtrodden children to emerge victorious by outwitting their tormentors through their resourcefulness and a little magic.

Initially, violence is used to reinforce the initial “victimhood” of the child, then it is repurposed in the latter stages of each tale to punish and overcome the perpetrator of the mistreatment.

James’s wicked aunts get their comeuppance when they’re squashed by the giant peach. In The BFG, kidnapped orphan Sophie emerges as the unlikely hero, saving herself and exerting a positive influence on her captor.

Dahl’s fiction is perhaps considered dangerous for a different reason: it takes children seriously.

The author dispenses humour alongside his descriptions of violence to create a less threatening atmosphere for young readers. Children revel in the confronting depictions even while being shocked or repulsed. Dahl — perhaps drawing on childhood trauma of his own — creates a cathartic outlet for children to release tension through laughter, especially at situations that may tap into the reader’s experiences of helplessness.

Such fiction provides children a means of empowerment. Seeing themselves reflected in literature can be an important part of a child’s processing of adversity.

Dahl’s work raises important questions about the safety of children, encouraging them to find their power in the most disempowering situations.

Written by Kate Cantrell, India Bryce and Jessica Gildersleeve. This article first appeared on The Conversation.