"There is great strength in vulnerability": Grace Tame’s surprising, irreverent memoir has a message of hope

Grace Tame’s The Ninth Life of a Diamond Miner shifts expectations. It’s not a minute-to-minute backstage account of the 12 months Tame spent as Australian of the Year, or the #LetHerSpeak campaign or the March4Justice.

It’s not wholly focused on her struggles with hostile elements in the commercial media or the former prime minister she calls “Scott” – which is only democratic after all, given “Scott” invariably called her “Grace”.

The book presents a horrifying account of being groomed and sexually abused as a 15-year-old by her 58-year-old schoolteacher, but it’s also not entirely taken up with “that part of my story that has been magnified and scrutinised publicly”.

What the book reveals is that while such events are “undoubtedly traumatic” they haven’t “defined” her “unfinished experience of life”.

And this is the important message of hope it gives to survivors of child sexual abuse. Until very recently, this crime was diminished or largely ignored by a culture that has historically labelled it a myth or moral panic, thereby enabling abusers. Meanwhile, as Tame writes, “they [abusers] deny, they attack, and they cry victim, while attempting to cast [victims] as the offenders”.

“Child abusers groom through isolation, fear and shame,” writes Tame. “Through the manipulation of our entire society. All of us, to some extent, have been groomed.”

Ahead of publication, Tame deleted her Twitter account. “I am aware this book will draw varying responses,” she writes, “including brutal backlash”. Pre-emptively responding to trolls and detractors, Tame says that she doesn’t “work for critics” but for “the people who find themselves in our words” and are “empowered by them”.

Instead, the book shares the larger story of Tame’s life in the hope that “my being vulnerable will permit the vulnerability of another”.

Mining for diamonds as an attitude to life

Unexpectedly, the memoir opens with the story of a man called Jorge – aged “67 or 76” – who Grace met in a ramshackle share house in Portugal at the age of 19. Jorge was “asset poor” but “story rich”. He had led “nine lives” in “seven different languages”, as a soccer player, a musician, a springboard diver, the former husband of a Jewish-American heiress and – like the figure in the book’s title – a diamond miner in Brazil. All that remained of these great adventures was an “overstuffed” chihuahua called Pirate and books of photographs.

An older, “healthily jaded” Tame suspects the chameleon-like Jorge was probably a con artist but writes that this “layer of delicious irony” merely served to confirm in her mind the things Jorge taught her that had “genuine value” – that life is essentially about people, experiences, authenticity, and connection. “Raw. Real. Uncut.”

Of course, it’s not Jorge but Tame herself who is the diamond miner in the book’s title. In this extended motif, diamond mining expresses an attitude to life.

“Some things in life are ultimately what we make of them,” writes Tame, “… there are things we can and cannot control” but “our power resides in how we respond to each”.

Inevitably, this sense of optimism is tempered with a warning. The “ninth life” of a cat is the point at which the creature becomes vulnerable.

For feminists of my own generation, who were taught that you had to be stronger, and tougher, and smarter just to get by, the book surprisingly reveals that “there is great strength in vulnerability”. Being vulnerable, says Tame, is about remaining open to life.

Tame writes about her aunts and cousins, about her parents’ divorce, her fight with anorexia, her neurodiversity, and the six years she spent living in the United States, where she moved aged 18. There’s her brief marriage to former Hollywood child star Spencer Breslin in 2017, with an Elvis-themed wedding, her friendship with actor John Cleese and his daughter Camilla, her work as an illustrator and indeed her brief stint working on a marijuana farm.

She writes about partying in California, hanging out in New York, and experimenting with drugs, which she says she no longer does. She has strong views on everything from the politics of Austrian novelist and playwright Peter Handke to her visit to the house of Frida Kahlo’s husband Diego Rivera in Guanajuato, Mexico.

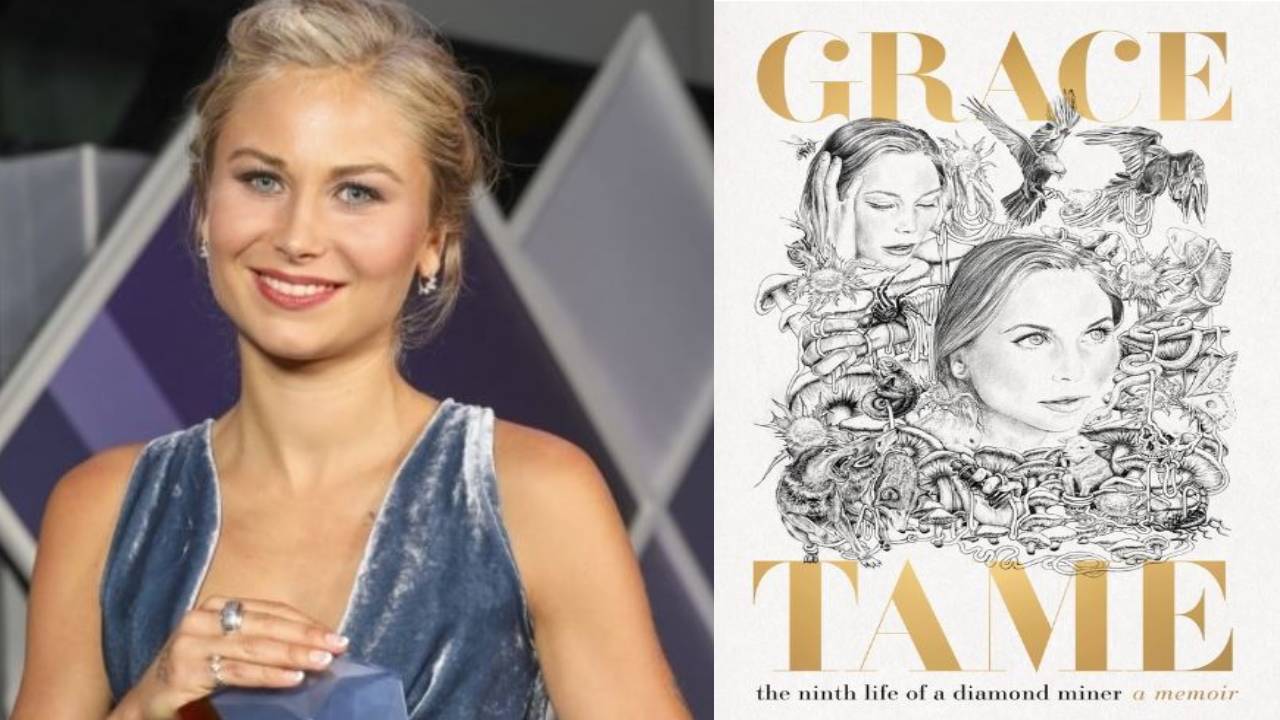

The book is loosely chronological, but mostly follows the rhythms and shapes of Tame’s thoughts. It is held together by a strong, irreverent, irrepressible voice, and is enclosed within a cover illustration that she drew herself.

Growing up neurodiverse

Tame was born in 1994, in Rokeby, a working-class suburb of Hobart, growing up in the same street as her aunts, cousins and grandparents, surrounded by a boisterous crowd of relatives who taught her, “Solidarity. And lots of love.”

She describes childhood days spent “climbing trees, jumping fences” and running in and out of cousin’s houses.

But she also recollects her childhood as a time of instability, being carted back and forth between the houses of two amicably divorced parents, which was, she says in retrospect, too much for a neurodiverse child.

“My mind sees time through the glass door of a front-loading washing machine on a never-ending spin cycle,” she writes. “I can pull out specific memories that look as clean as yesterday because at any given moment everything is churning at high speed in colour”.

She quickly learnt “mimicking and masking”, the “survival strategies” of autistic women. Much later, she would find out that neurodiversity can also be a strength. Tame calls herself “the autistic artist who finds everyday socialising harder than calculus, but walking onto a stage as easy as kindergarten maths”.

She is at pains to point out that although she has “seen some strife” – unlike the former prime minister’s characterisation of her as person who has had “a terrible life” – “on the whole” her life has been mostly “wonderful”.

Abuse

But in the background was “our family’s sixth spidery sense”, largely directed at divining the presence of huntsmen, which Tame learnt to carry out of the house “by the leg”. Aptly, this description foreshadows her encounter with the “rock spider” Nicolaas Bester, the serial sex offender lurking in the private Anglican girls’ school for which Tame’s mother, aspiring to a better education for her daughter, worked hard to pay the fees.

Bester began preying on Tame at age 15 in “the very same year my mental health began to decline”. The grooming started in the classroom with Bester telling what he claimed were jokes. Once, about a student “obsessed with tubular objects”. At another time, about a former student who he claimed was “as easy as a McDonald’s drive-through”.

Through “innocent, permissive laughter” students became acquainted with a “supposedly harmless man”. His “recycled racy comments were just part of his schtick, and they didn’t alarm our young inexperienced minds in the same way they might have adults”.

Nobody suspected there was something fundamentally wrong in all this, alleging “he pushed the boundaries, that was all”.

Bester soon began following Tame about, attempting to gain access by pretending to be her uncle at a medical facility where Tame was being treated, also turning up at the kiosk where she had a part-time job.

Tame’s parents had two consecutive meetings with the school, asking them to put an end to Bester’s “inappropriate behaviour”. But Bester “coolly laid the groundwork for a narrative in which I was the supposed aggressor, and mentally ill one that he felt ‘sorry for’.” And the school, she writes, believed him. “This would, in fact, be his line of defence in court.”

The police statement given by the school principal was, she argues, “perversely, almost as damning of the school as it was of him”.

It revealed that “despite regular and consistent complaints from students, staff, parents and visitors to the institution” the school “allowed him to continue working”.

Police found “videos of adults raping children on his computer”.

Tame writes that after she disclosed the sexual abuse by Bester, the school sent her mother a bill for outstanding fees.

Bester was sentenced to two years and 10 months in jail in 2011 for the abuse of Tame. Yet, writes Tame, he was surrounded by apologists. His church group invited him back to play the organ as soon as he was released. On social media, or simply standing on the street outside a nightclub, Tame was surrounded by a barrage of victim-blaming abuse.

Advocacy and the media

Over time, the media narrative around child sexual abuse has begun to shift, due to the public advocacy of countless men and women, including Tame. But the change is inconsistent and uneven.

In 2018, Tame teamed up with Nina Funnell, a Walkley Award winning freelance journalist and sexual assault survivor who began the #LetHerSpeak campaign in partnership with Marque Lawyers and End Rape On Campus Australia. The campaign was aimed at overturning the gag clauses in Tasmanian and Northern Territory law. In 2019, Tame won a supreme court exemption to tell her harrowing story of being groomed by Bester.

Advocacy takes its toll, she writes, in “the re-traumatisation that results from reliving the abuse.” It is predicated on an incessant “unpacking and processing”, with the reality of abuse “playing on a loop”.

All the while Tame says she has been called everything from a “feminist hero of the fourth wave” to a “man-hater” and a “transgender child abuser”.

The brief accounts Tame gives of her interactions with commercial television producers and journalists are far from flattering to the media. Though she looks strong, the media furore frequently left her “shaking”.

I’d never had such intense panic attacks, coloured by flashbacks cut with criticisms so violent that all I could hope to do was knock myself out in the hopes of knocking them out of me.

And there were, consequently, missed opportunities. The 2021 National Press Club address “in which I talked about how the media retraumatises survivors by not listening closely to the boundaries they set” was “overshadowed that day by a confected feud” between Tame and the former prime minister “that then spiralled and became an ongoing convenient media distraction used to dilute the work I did.”

Other media encounters are slammed as “trauma pornography in disguise” and the “unethical, disingenuous gathering of vulnerable people for the purpose of entertainment”.

Towards the end of the book Tame recounts the frenzied criticism generated by the so called “side-eye” moment, where she was photographed with then PM Morrison at this year’s morning tea for Australian of the Year recipients.

In the wake of these photographs, she writes, her partner Max Heerey was “sent a barrage of text messages” including repeated messages from one journalist asking whether her “autism” had “something to do with” her frosty exchange with Morrison and if “I frowned because I was autistic”.

At this point, Max informed the journalist that their questions were ableist and “incredibly offensive”.

“I have no idea if it’s offensive or true or what but just wanted to ask as it’s a discussion being raised,” the journalist shot back, followed by a screenshot sampling an article citing autistic “so-called ‘social-deficits’”.

“I said please don’t contact me again. This is all incredibly offensive,” Max repeated. “Grace is autistic but not stupid”.

But the texts kept coming.

Tame writes,

I didn’t frown at the Prime Minister because I can’t control my face, because I’m disabled, because I have some kind of deficit, or because I need help. I didn’t frown at him because, in his words, ‘I’ve had a terrible life’’".

I frowned at Scott Morrison deliberately because, in my opinion, he has done and assisted in objectively terrible things.“

Without specifying what those things are, Tame writes, "No matter what your politics are, the harm that was done under his government was … not limited to survivors of domestic and sexual violence”.

To have “smiled at him” would have been a lie.

In place of confected outrage, which is “disturbingly skewed”, this memoir attempts to “bridge gaps in understanding” and “ignite a conversation”. It’s worth the “risk and pain”, Tame writes, because “evil thrives in silence”.

This article originally appeared on The Conversation.

Images: National Press Club of Australia/Macmillan