From Fendi to fungi – your next handbag could be made from mushrooms

It might be time to switch your handbag from Fendi to fungi, say researchers. They have harnessed the power of the humble mushroom to convert food waste into sustainable faux leather, paper and cotton substitutes.

Presenting their results at a virtual meeting of the American Chemical Society (ACS), the researchers say that this fungal leather takes less time to produce than existing substitutes already on the market, and, unlike some, is 100% bio-based.

Their efforts tie together two enormous, but seemingly unrelated, environmental concerns. Cotton, petroleum-based synthetic fibres, paper and leather are all beset with ecological woes, ranging from water demand to contributions to climate change and the ethical treatment of animals. Meanwhile, plenty of food goes to waste.

Setting out to resolve the whole suite of issues in one fell swoop, lead investigator Dr Akram Zamani and her team in Sweden have developed a range of sustainable materials derived from fungi.

“We hope they can replace cotton or synthetic fibres and animal leather, which can have negative environmental and ethical aspects,” says Zamani.

They’re not the first group to have produced a fungal leather, but according to Zamani, they are the first to have made a product with properties that can match real leather, and at a production rate that could realistically match market demands.

Although there is little available information on the production process of existing fungal materials, Zamani says it appears that most are made from harvested mushrooms or from fungus grown in a thin layer on top of food waste or sawdust using solid state fermentation. Such methods require several days or weeks to produce enough fungal material, she notes, whereas her fungus is submerged in water and takes only a couple of days to make the same amount of material.

In addition, some of the fungal leathers on the market contain environmentally harmful coatings or reinforcing layers made of synthetic polymers derived from petroleum, such as polyester. That contrasts with the University of Borås team’s products, which consist solely of natural materials and will therefore be biodegradable.

“In developing our process, we have been careful not to use toxic chemicals or anything that could harm the environment,” says Zamani.

So how do they go about the transformation of mushrooms to materials? It all starts with fattening up your chosen fungus.

Fungi are hungry little organisms. To feed their cultivated fungal strain – Rhizopus delemar, commonly found on decaying food – the team collected unsold supermarket bread, which they dried and ground into breadcrumbs. As the fungus fed on the bread, it produced microscopic natural fibres made of chitin and chitosan that accumulated in its cell walls.

After two days of feeding, the scientists collected the cells and removed lipids, proteins and other by-products that they say could potentially be used in food or feed. But what they were really after was the jelly-like residue left behind – a goop consisting of the fibrous cell walls that was then spun into yarn, which could be used in sutures or wound-healing textiles and perhaps even in clothing.

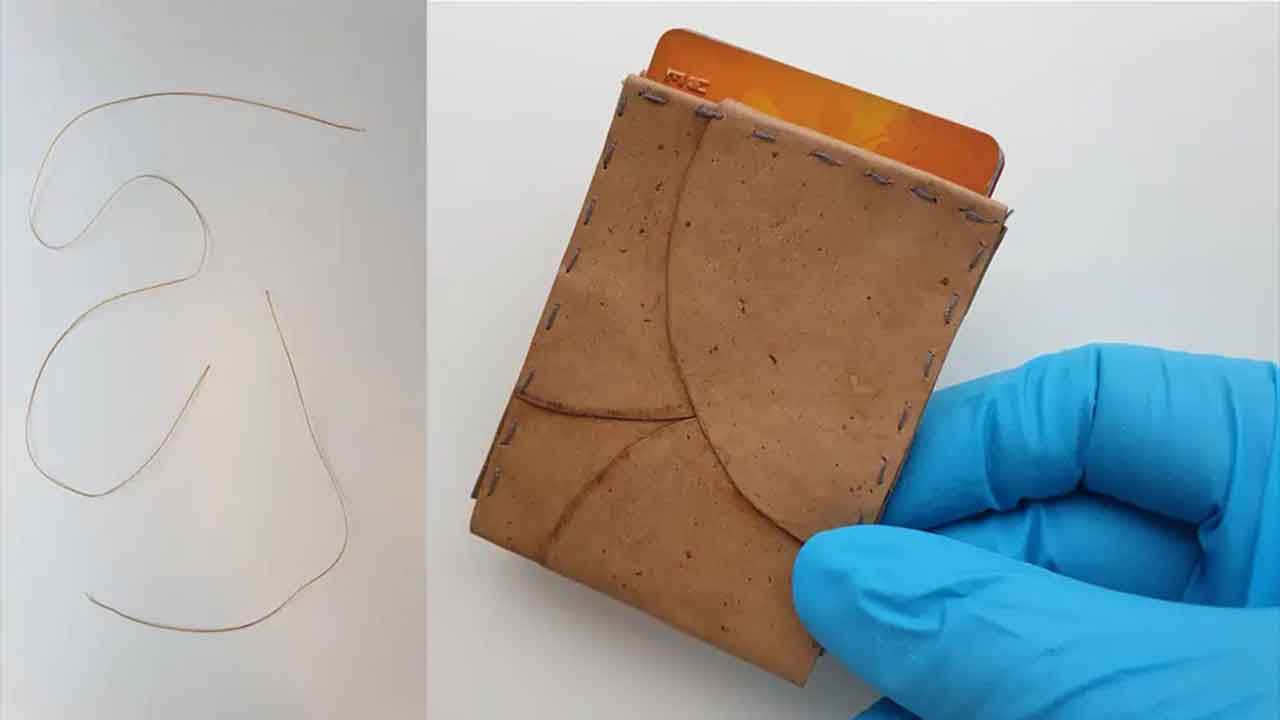

In an alternative method, the suspension of fungal cells was laid out flat and dried to make paper- or leather-like materials.

Through a series of trial-and-error tests, the team has now developed materials made from multiple layers of these fungal sheets. The composites are treated with tree-derived tannins to give them softness, and alkalis to give them strength. Finally, strength, flexibility and glossiness are all improved by treatment with glycerol and a bio-based binder. The end result is a material that very closely mimics real animal leather.

“Our recent tests show the fungal leather has mechanical properties quite comparable to real leather,” Zamani says.

The team is working to further refine their fungal products. They recently began testing other types of food waste, including fruits and vegetables – particularly the mushy pulp left over after juice is pressed from fruit. “Instead of being thrown away, it could be used for growing fungi,” Zamani says. “So we are not limiting ourselves to bread, because hopefully there will be a day when there isn’t any bread waste.”

This article was originally published on Cosmos Magazine and was written by Jamie Priest. Jamie Priest is a science journalist at Cosmos. She has a Bachelor of Science in Marine Biology from the University of Adelaide.

Image: Akram Zamani