Producing electricity from your sweat might be key to next wearable technology

Imagine a world where the smart watch on your wrist never ran out of charge, because it used your sweat to power itself.

It sounds like science fiction but researchers have figured out how to engineer a bacterial biofilm to be able to produce continuous electricity from perspiration.

They can harvest energy in evaporation and convert it to electricity which could revolutionise wearable electronic devices from personal medical sensors to electronics.

The science is in a new study published in Nature Communications.

“The limiting factor of wearable electronics has always been the power supply,” says senior author Jun Yoa, professor of electrical and computer engineering at the University of Massachusetts Amherst (UMass), in the US. “Batteries run down and have to be changed or charged. They are also bulky, heavy, and uncomfortable.”

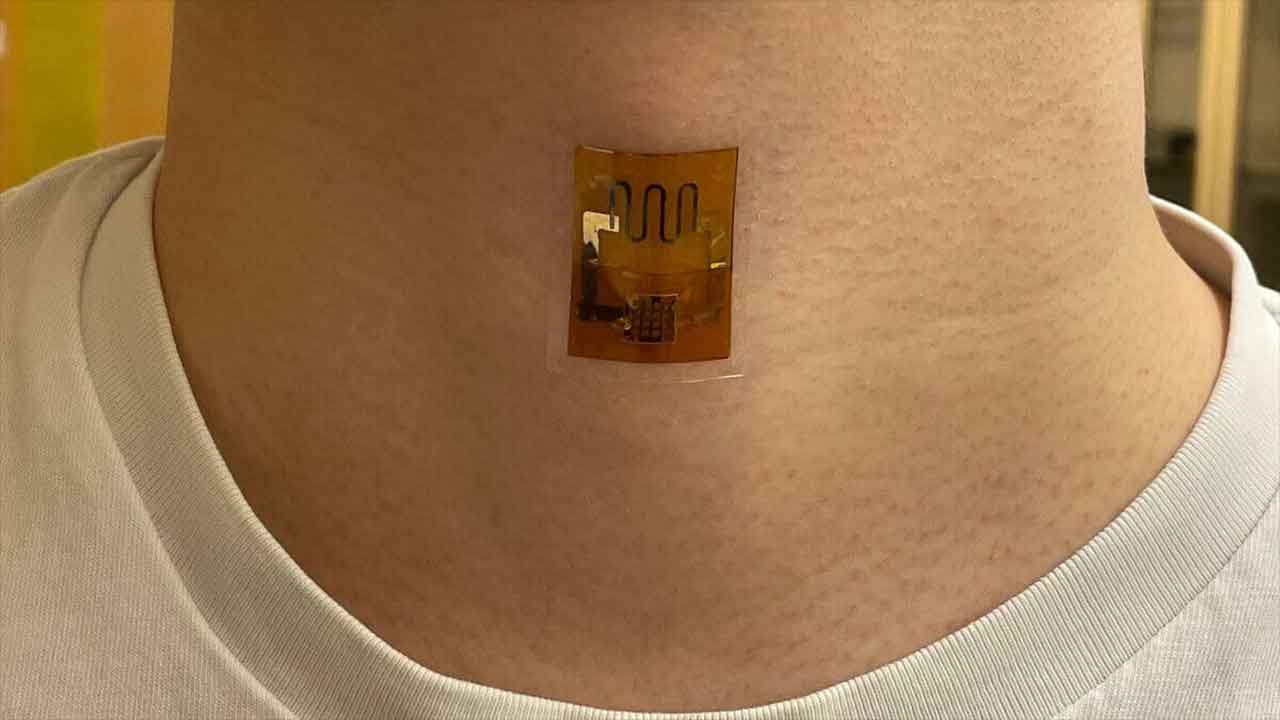

But the surface of our skin is constantly moist with sweat, so a small, thin, clear and flexible biofilm worn like a Band-Aid could provide a much more convenient alternative.

The biofilm is made up of a sheet of bacterial cells approximately 40 micrometres thick or about the thickness of a sheet of paper. It’s made up a genetically engineered version of the bacteria Geobacter sulfurreducens to be exact.

G. sulfurreducens is a microorganism known to produce electricity and has been used previously in “microbial fuel cells”. These require the bacteria to be alive, necessitating proper care and constant feeding, but this new biofilm can work continuously because the bacteria are already dead.

“It’s much more efficient,” says senior author Derek Lovley, distinguished professor of Microbiology at UMass Amherst. “We’ve simplified the process of generating electricity by radically cutting back on the amount of processing needed.

“We sustainably grow the cells in a biofilm, and then use that agglomeration of cells. This cuts the energy inputs, makes everything simpler and widens the potential applications.”

The process relies on evaporation-based electricity production – the hydrovoltaic effect. Water flow is driven by evaporation between the solid biofilm and the liquid water, which drives the transport of electrical charges to generate an electrical current.

G. sulfurreducens colonies are grown in thin mats which are harvested and then have small circuits etched into them using a laser. Then they are sandwiched between mesh electrodes and finally sealed in a soft, sticky, breathable polymer which can be applied directly onto the skin without irritation.

Initially, the researchers tested it by placing the device directly on a water surface, which produced approximately 0.45 volts of electricity continuously. When worn on sweaty skin it produced power for 18 hours, and even non-sweating skin generated a substantial electric output – indicating that the continuous low-level secretion of moisture from the skin is enough to drive the effect.

“Our next step is to increase the size of our films to power more sophisticated skin-wearable electronics,” concludes Yao.

The team aim to one day be able to power not only single devices, but entire electronic systems, using this biofilm. And because microorganisms can be mass produced with renewable feedstocks, it’s an exciting alternative for producing renewable materials for clean energy powered devices.

This article was originally published on Cosmos Magazine and was written by Imma Perfetto. Imma Perfetto is a science writer at Cosmos. She has a Bachelor of Science with Honours in Science Communication from the University of Adelaide.

Image: Liu et al., doi.org/10.1038/s41467-022-32105-6