Meet Benjamin Jesty: The unsung hero of vaccinations

More than 250 years before the first case of COVID-19 was announced, another deadly virus - smallpox - was spreading across Europe.

The smallpox epidemic led to the development of the first vaccine, credited to Gloucestershire physician, Edward Jenner.

However, the technique which Jenner became famous for had been pioneered more than 20 years earlier by a Dorset dairy farmer whose social status prevented him from receiving any credit.

It wasn’t until microbiologist Patrick Pead, who was holidaying in Dorset in 1985, found a booklet in a Worth Matravers village called ‘Benjamin Jesty: The First Vaccinator’.

“I thought ‘that’s not right, it was Edward Jenner’,” he said.

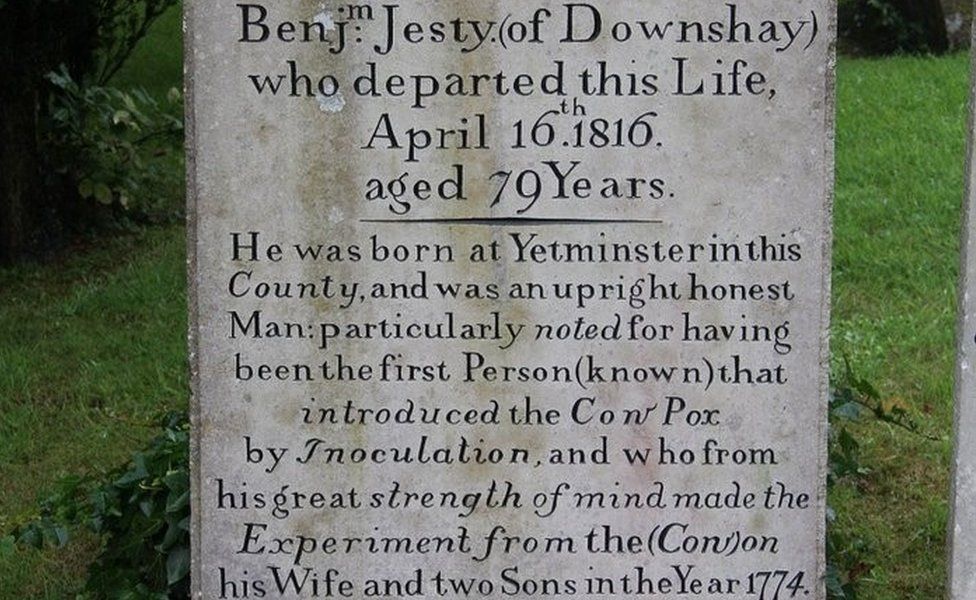

“We went to the churchyard and saw his tombstone and that day changed my life.”

Image: Julia&keld / Find a Grave

Over the following years, Pead went to work, piecing together what little information was known about Jesty.

This included the tracking down of the only portrait of the famer, which was believed lost for more than a century before it turned up on the other side of the world.

Jesty’s story starts in 1774, when the farmer deliberately infected his family with cowpox to protect them from the smallpox virus, which was the leading cause of death at the time.

Most people became infected during their lifetimes, with about 30 percent of those infected not surviving.

However, Jesty had contracted cowpox as a boy and knew that milkmaids seemed to somehow be immune from smallpox.

Using pus taken from lumps on a cow’s udder, he scratched the infectious material into the skin of his wife and two sons using a stocking needle.

Though his wife eventually recovered after being seriously ill, Jesty was vilified.

“The last trial for witchcraft had been less than 40 years earlier,” Pead said.

“Jesty was reviled, people were suspicious.

“In those days, everybody would go to church on Sunday and the human body was sacred but here was a guy taking something from a beast and poking it into a human body.”

Jesty’s experiments were later proved to be successful after attempts to infect his sons with smallpox failed, indicating they were immune.

Edward Jenner is believed to have heard of Jesty’s experiments through his dining club, carried out a similar test in 1796 on an eight-year-old boy, but his findings were rejected by The Royal Society.

After additional experiments, and with support from his colleagues and the king, Jenner was awarded a total of £30,000 ($AUD 56,270 or $NZD 59,360) by parliament between 1802 and 1807.

But, Jesty’s efforts were not unrecognised, with doctors and clergy calling for his recognition in the discovery.

Despite their attempts to give him credit where it was due - including in the commission of Jesty’s portrait - Jenner’s well-connected supporters succeeded, leaving Jesty to become a footnote in the history of medicine.

In his quest to uncover more about Jesty, Mr Pead was able to locate the portrait - which had passed to the Pope family of the Eldridge Pope Brewery in Dorchester - after receiving the phone number of a Pope family descendent in South Africa.

“I rang them straight away - it was about 10 o’clock at night. They said, ‘it’s hanging here above the fireplace in the family home’,” he said.

After a drawn-out process, the portrait returned to the UK and was restored over two years.

The painting finally went on display, first in Dorchester’s Dorset Museum, then at the Wellcome Collection galleries.

Interest in Jesty’s story has grown ever since, and Pead has written books and articles, given hundreds of talks, and was awarded a Fellowship of the Historical Association for his efforts.

“I’m a scientist working in medicine and I know all of the progress is built on the findings of others,” he said.

“Vaccination wasn’t plucked out of the air by Benjamin Jesty or by Edward Jenner, it was built on out of what went before - that’s why Jesty does deserve recognition.”

Image: Wellcome Collection