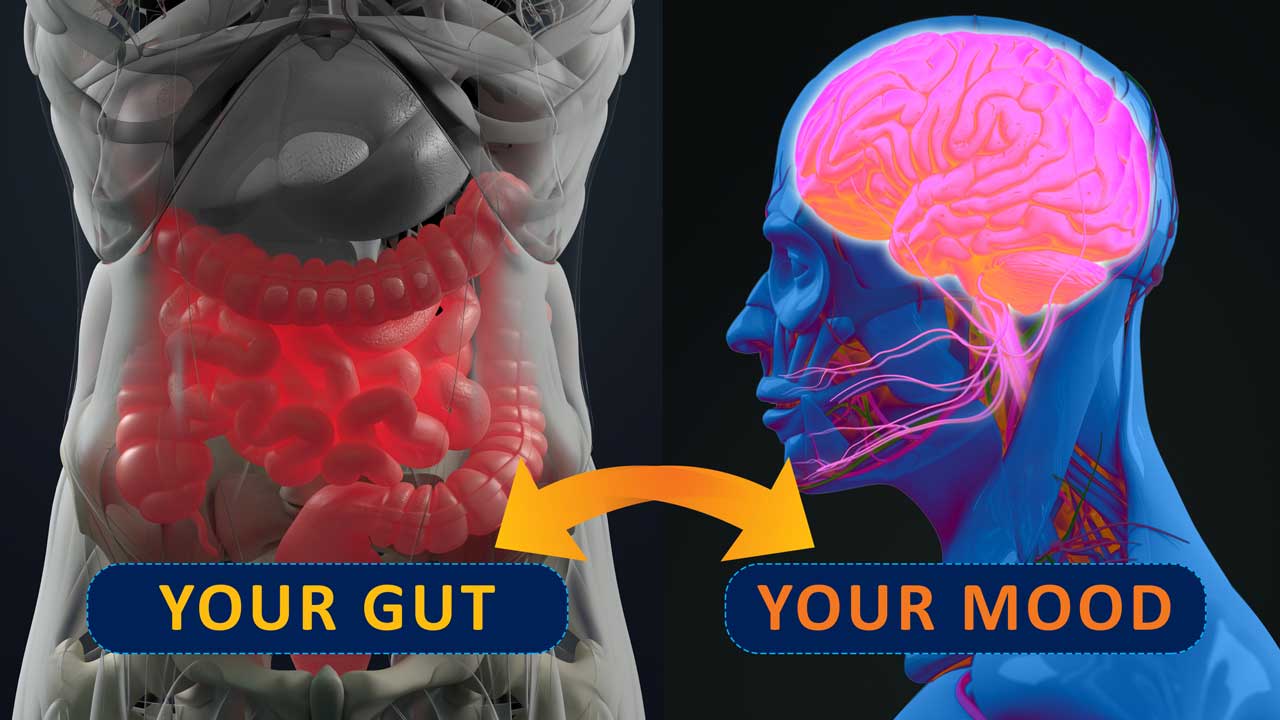

How gut bacteria could affect your mental health

As we continue to investigate the causes and potential treatments of mental health disorders, a growing amount of evidence suggests the microscopic inhabitants of our gut can impact our mental health.

“If you would have asked a neuroscientist 10 years ago whether they thought the gut microbiota could be linked to depression, many of them would have said you were crazy,” said Jeroen Raes, a systems biologist and microbiologist at KU Leuven in Belgium.

What is the gut microbiome?

Microbes, which include bacteria, viruses, fungi, and other microscopic living things, live inside the intestines and on the skin.

Most of the trillions of these microbes live in a “pocket” of the large intestine called the cecum, and are known as the gut microbiome.

The majority of the microbes studied so far have been bacteria, and up to 1000 species can live in the gut. Each species plays a different role in the body, with some being extremely important for your health and others potentially causing disease.

Bacteria and mental health

Decades of animal model research and small studies of humans have pointed to a link between mental health and the gut microbiome, with researchers now attempting to identify the specific microbes that could be influencing the brain.

For example, a study published by Raes and colleagues in Nature Microbiology examined the correlation between features of a person’s microbiome, their quality of life, and their level of depression. The researchers found that patients with depression had lower levels of two species of bacteria - Coproccus and Dialister - when compared to healthy controls.

A separate team later reported the abundance of several types of bacteria correlated with the severity of schizophrenia. They also found that individuals with schizophrenia could be frequently differentiated from healthy subjects based on the presence of specific microbes.

Another study looking at the mechanisms that could drive these mental health disorders transplanted stool samples into mice and monitored their behaviour. They found that mice receiving transplants from schizophrenia patients were more hyperactive and exerted more effort during a swim test than mice receiving stool transplants from healthy patients. The mice also had different levels of neurotransmitters which are essential for brain function, and the levels in the brains of mice with transplants from schizophrenia patients reflected the chemical patterns found in the patients, according to study coauthor Julio Licinio, a psychiatrist at SUNY Upstate Medical University in Syracuse.

Why this matters

Though research in mice might be less translational to humans, these studies are useful for finding markers that could be tested to aid in diagnosis.

To negate factors such as stress that could affect the behaviour of the mice, Raes and his colleagues’ study looked at the microbiome differences between healthy and depressed individuals.

The bacteria they found were missing in depressed individuals were examined to determine whether they could produce or break down neuroactive compounds in the gut.

For example, the genomes of Coproccus contain DNA sequences that can generate DOPAC, a product of breakdown of dopamine, which is associated with depression when depleted.

Though the findings don’t confirm that lower levels of these species of bacteria correlate with depression, they offer a potential direction for possible pathways and therapeutic targets for these mental health disorders.

“Microbiology is not simple, because it involves ecologies,” said University of Florida psychologist Bruce Stevens. “You can’t take down one bacterium without taking down the whole nest, so translation to treatment is going to be tough. A single species won’t do it.”