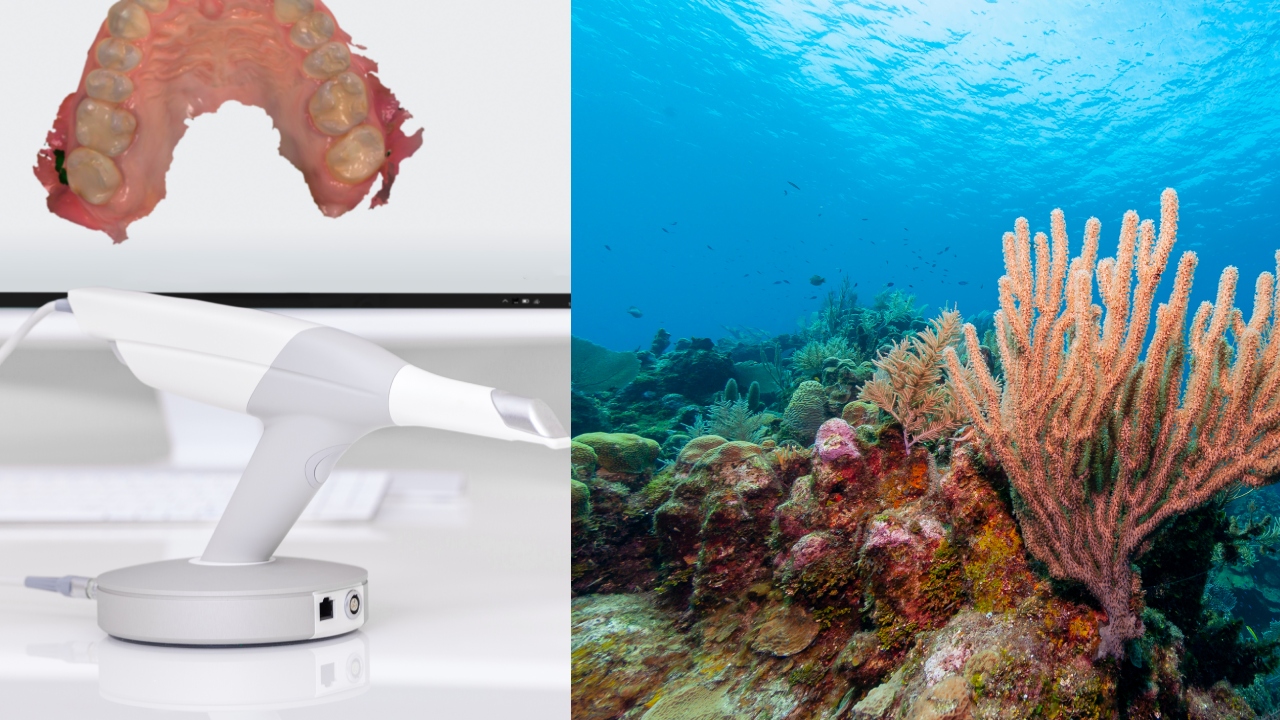

Using a dental scanner on corals like a “magic wand”

Dr Kate Quigley’s trip to the dentist might have revolutionised coral reef research.

The intra-oral dental scanner her dentist was using turned out to be the perfect thing for scanning baby corals and learning critical information about their growth.

“Baby corals and teeth are actually not too different. They’re both wet,” says Quigley, now a senior research scientist at the Minderoo Foundation.

“Which might not seem like a big deal – but if you’re scanning something, that creates diffraction. […] Having tech that can work in a wet environment and handle a texture that’s wet, is actually really important.”

There are a few other things that bring dental scanners and coral together, too.

“The properties of teeth and baby coral skeletons are very similar. They’re calcium-based, slightly different, but similar enough that the resolution of the laser was tailored to coral skeletons, just by accident,” says Quigley.

While conducting research at the Australian Institute of Marine Science (AIMS) and James Cook University, Quigley managed to get one of the tooth-scanning devices she’d seen at the dentist (the ITero Element 5D Flex), and test it on corals.

Quigley has published a description of the new method in Methods in Ecology and Evolution.

Monitoring coral growth is key to restoring and preserving it.

“Growth and survival are really the currency of any monitoring program. It doesn’t matter what organism you’re looking at,” says Quigley.

But it’s very difficult to monitor the growth of corals – because of their shape and size.

“How most coral growth studies are done is really just taking 2D flat images. And that works really well when the coral is really young, say a month or two months, because they’re like little flat pancakes,” says Quigley.

As they grow, corals develop very complex three-dimensional structures. Scanning these structures is time-consuming, and often destructive: the coral has to be killed in order to be scanned.

The dental scanner takes quick, harmless scans and uses AI to combine the images into a 3D picture almost immediately.

“Instead of taking all day and into the night, it takes two minutes,” says Quigley.

It also provides better detail.

“Baby corals start off really small. They’re almost invisible,” says Quigley.

“Being able to measure those really fine scale differences, smaller than a millimetre, was also really important.”

Quigley describes the scanner as “effectively a magic wand”.

So far, the scanner’s been shown to work in a lab (at AIMS National Sea Simulator) and in the field – on a boat above the water.

Unfortunately, it’s not waterproof enough to take diving. Yet.

Quigley hopes it will become a regular tool used by coral researchers and restorers.

“If we are thinking about scaling up reef restoration in the future we’re going to need a way to measure and monitor these individuals more effectively. It wouldn’t be sustainable if it’s one individual a day.”

Quigley says that this discovery demonstrates the importance of thinking laterally.

“In science I feel like there’s less and less room to just be creative anymore,” she says.

“This has been a really interesting time for me – to dabble in dentistry and look at all the tech that’s available and may be useful in conservation.”

This article originally appeared on cosmosmagazine.com and was written by Ellen Phiddian.

Images: Shutterstock